SB Television

A New Angle on Speed: Poling the Headsail

When sailing at broad angles, a 150-percent genoa sets properly from a standard-length pole, squared aft.

Billy Black/Sailing World Archives

When sailing at broad angles, a 150-percent genoa sets properly from a standard-length pole, squared aft.

Billy Black/Sailing World Archives

Editor’s Note: Ed Adams was Senior Editor At Large for Sailing World. His story “A New Angle on Speed” was originally published in the January 1996 issue of Sailing World.

Bob Johnstone was surprised by what we learned. I wasn’t. After years of sailing “chuteless” small boats like Snipes and Stars, I knew that racing with a whisker pole was not as straightforward as it appeared. So, when we set out to test angles, speeds and PHRF sail-trim techniques onboard Johnstone’s J/42 Gannet, I was sure the results would be enlightening.

Our conclusions were put to another test one week later when Gannet entered the New York YC Chesapeake Cruise. The second race was typical. While most of the cruising canvas fleet ran wing-and-wing, limping along at a snail’s pace in 5 to 8 knots of wind, Johnstone took a different track. Instead of poling his genoa out to windward, he poled it out to leeward and reached up, sailing faster angles and jibing downwind. Gannet won the race by over 7 minutes. In fact, Gannet won all of the races, some by as much as 17 minutes.

Coming from a lifetime of sailing with spinnakers, Johnstone learned that sailing with a whisker pole can be just as much of a tactical challenge. And when done with the same attention you might give a spinnaker, the difference in performance can be astounding. You don’t need an army of crew to go fast with a whisker pole; all you need to know is which course to steer and how to trim the sails.

The Ideal Whisker PoleThe pole you’d like to use is not the same pole you’re allowed to use. The ideal pole would be of infinitely adjustable length. PHRF rating penalties, however, restrict pole length to that of a boat’s J dimension (the distance between the mast and forestay tack). This is done so that a standard spinnaker pole can double as a whisker pole.

Why is it fast to have a long, adjustable whisker pole? Take a look at how a non-spinnaker boat performs at various angles to the wind. First, picture a boat running dead downwind. At this angle, a standard-length pole is adequate for sailing with a 150-percent genoa. With the pole squared aft for running (see photo, left), the foot of the genoa is stretched just tight enough to project plenty of sail area to the wind.

Now head up onto a broad reach. As you head up, the pole must be eased forward, or the wind will get behind the leech of the genoa and cause the sail to collapse. But as the pole is eased forward, the tension on the foot relaxes, and the lower half of the sail balloons, becoming full and inefficient. As it balloons, projected area is lost.

The pole also tends to lift as it is eased forward. This eases the leech of the genoa, letting the upper portion of the sail twist out in front of the boat. Attaching the foreguy to hold the pole down, or moving the sheet lead forward, corrects over-twisting. But you’re still left with inadequate foot tension.

There are only two ways to keep the foot stretched tight as the pole is eased forward: either lengthen the pole or shorten the foot. As you would expect, lengthening the pole is preferable. If the pole could be extended to twice the length of J, you could nearly beam reach. With the sails set wing-and-wing, a pole that is 1.5 times the J dimension would still provide markedly improved speed at most reaching angles.

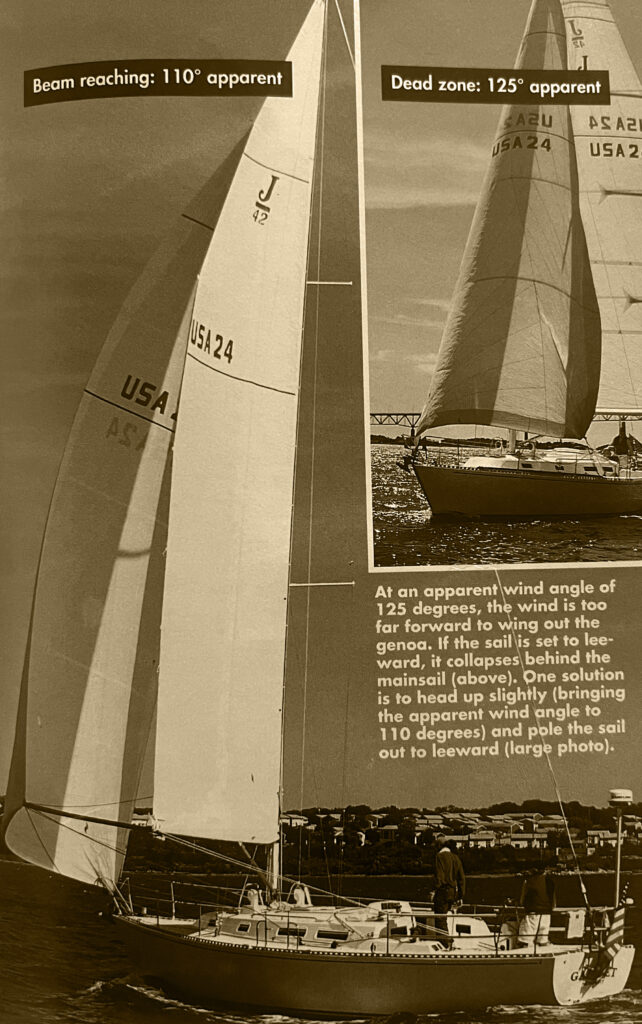

Gannet beam reaches at 110-degree apparent (left) and at 125-degree apparent (right), aka the “dead zone.”

Billy Black/Sailing World Archives

Gannet beam reaches at 110-degree apparent (left) and at 125-degree apparent (right), aka the “dead zone.”

Billy Black/Sailing World Archives

It’s too bad that PHRF hits you with a nasty penalty for a long pole. Since this leaves you stuck with a standard-length pole, the other option is to shorten the foot of the genoa when reaching wing-and-wing. As the pole is eased forward, a smaller genoa of full hoist would, theoretically, be faster despite what you might think. A smaller overlap wouldn’t project less area, as projection is controlled by pole length; it would present a more efficient and less ballooned shape.

In our test, we tried roller reefing the genoa to 130 percent when reaching wing-and-wing. It didn’t prove to be an advantage because we lost too much sail area in the head of the sail. The foot trimmed correctly, but the sail area aloft was simply too small — to make a smaller sail efficient at tighter angles, the sail would have to be full hoist.

In practical terms, a shorthanded, cruising canvas crew will not be able to douse and change genoas with every wind shift. They have to deal with one 150-percent sail and one undersized fixed-length pole. Hence, they also have to learn how to deal with sailing in the “dead zone.”

Dodging the Dead ZoneWhen sailing with a spinnaker, it never pays to aim the boat dead downwind. That’s because the boat sails so much faster when you head up. For every degree the boat turns toward a reach, the boatspeed climbs. It climbs so fast that it pays to reach back-and-forth, sailing a zig-zag jibing course toward the leeward mark. The angle chosen depends on how windy it is. But one thing holds true: the higher you sail with the spinnaker, the faster you go.

This axiom doesn’t hold for sailing with cruising canvas and a standard PHRF whisker pole. Imagine sailing on a close reach: On this point of sail, both the main sail and genoa are full and drawing with maximum pressure. Now bear off onto a beam reach. As you bear off, the leech of the genoa will fall into the wind shadow of the mainsail. The main will still draw hard, but the pressure on the genoa well soften. At this point, the wind angle is too far forward to set a standard whisker pole.

Now bear off another 15 degrees: As you do, more of the genoa becomes blanketed. Continue to head down and the genoa will eventually hang limp, with little wind hitting the luff, and this being inadequate to lift the clue (see inset photo). When this happens, you have entered the dead zone.

On this point of sail, the genoa can be filled to weather with a whisker pole. While this is faster than letting the genoa hang limp to leeward, the wind is still too far forward for the sail to fly efficiently with a short, PHRF-mandated pole.

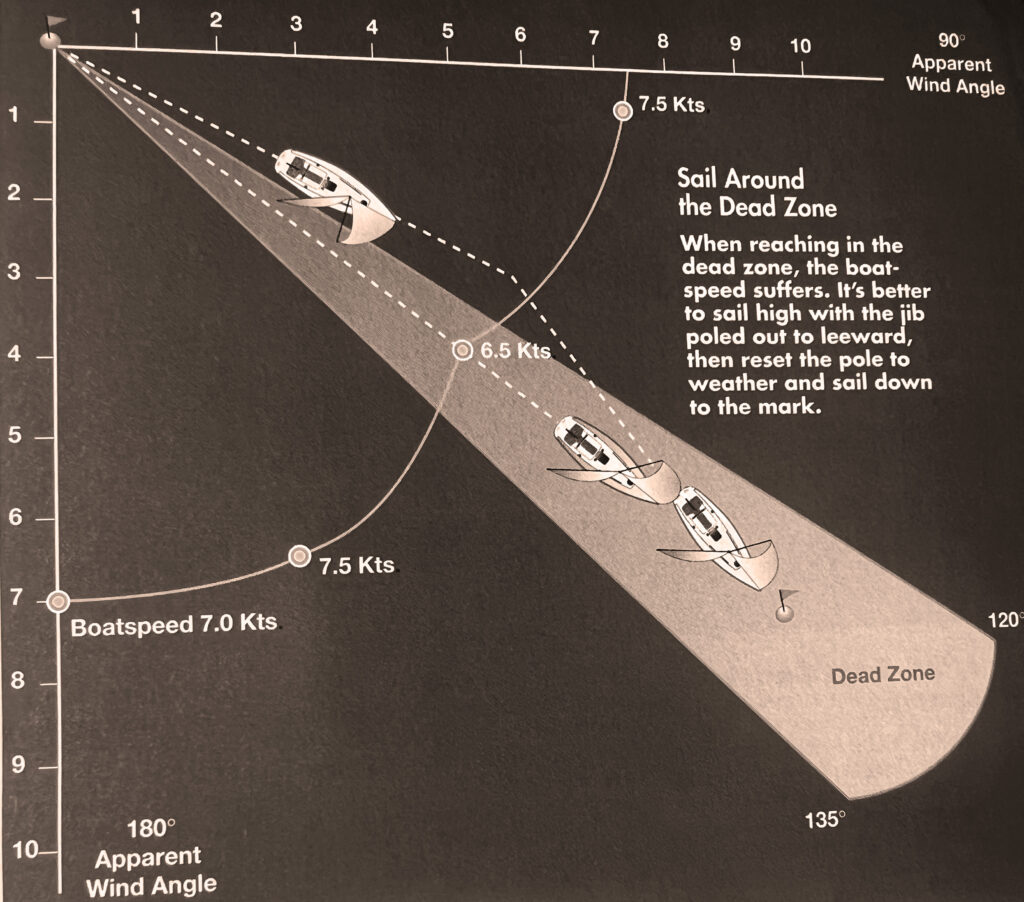

If you bear off even further, and the whisker pole is squared, sail shape improves and the boatspeed improves. This is where sailing with cruising canvas differs from sailing with a spinnaker. As you bear off with a spinnaker, the boatspeed always drops. With a whisker pole, as you bear away from the dead zone, boatspeed climbs initially. Then, when approaching dead downwind, the speed begins to fall off again. When expressed as a “polar curve,” which plots a boat’s potential speed against its sailing angle, the dead zone appears as a hump in the curve, a point where the boat is unnaturally low on a reach (see illustration).

When reaching in the dead zone, the boatspeed suffers. It’s better to sail high with the jib poled out to leeward, then reset the pole to weather and sail down to the mark.

Rachel Cocroft/Sailing World

When reaching in the dead zone, the boatspeed suffers. It’s better to sail high with the jib poled out to leeward, then reset the pole to weather and sail down to the mark.

Rachel Cocroft/Sailing World

Let’s say you round the weather mark and set off toward the reach mark. If the course to the reach mark is in the dead zone, there are two choices: You could sail straight toward the reach mark with a whisker pole set. The genoa would balloon inefficiently because the pole is too short. The boat wouldn’t be going particularly fast, but at least it would be sailing straight line, which is the shortest course.

Alternatively, you could set the jib to leeward and reach up above the course to the mark, sailing a faster angle. Then, when positioned well to weather of the rhumbline, you could bear off and sail wing-and-wing on a broad reach to the mark at an equally fast angle. By sailing a longer distance, the dead zone is avoided. But does the extra speed make up for the extra distance? That was one of the primary questions answered in our test.

Here’s What We LearnedTo chart the territory in and around the dead zone, we spent a day recording Gannet’s boatspeed at various sailing angles and with a variety of sail-trim configurations. After averaging and plotting the data, we came up with a number of conclusions. Some were surprising, like the advantage of poling the genoa out to leeward. Others were more predictable such as, when reaching wing-and-wing, roller furling the genoa doesn’t pay.

To make the lessons from the test easier to apply to real-life situations, here are some rules of thumb to follow.

Try the Pole to LeewardWhen tight reaching, most sailors know that it’s fast to move the genoa sheet lead forward and outboard to the leeward rail. After bearing off further, toward a beam reach, flat-out raceboats throw up the spinnaker; they need an alternative to maintain speed. When the apparent-wind angle is aft of 80 degrees, that alternative is to pole the genoa out to leeward.

This technique works with a 150-percent genoa from apparent wind angles of 80 to 120 degrees. The pole holds the clew of the sail outboard, away from the blanket of the mainsail by tensioning the foreguy, the pole acts a vang to control genoa leech tension; but be careful not to over-vang—you don’t want the pole to drag in the water when the boat heels in a big puff.

The foreguy should be adjusted so the sail breaks evenly from head to tack as the sheet at ease. Tensioning the foreguy has an effect similar to moving the genoa lead forward: If the sail is breaking earlier at the head, tensioning, the foreguy will correct it. This setup produces far more power than “free flying” the sail without a pole in the lee of the mainsail.

At apparent wind angles of 100 to 120 degrees, the pole should be set to leeward at full length. At angles of 80 to 100 degrees, a standard pole is too long to trim the sail properly. The foot of the genoa becomes strapped when the sail is sheeted in. The solution is to shorten the effective length of the pole. Tie a loop of line through the clue of the jib, and clip the pole to the loop. Adjust the length of the loop so as to shorten the effective length of the pole 1 to 2 feet. Then, as you trim the sail, the foot will stay full enough for adequate power. (See photo beam reaching: 90 degrees apparent)

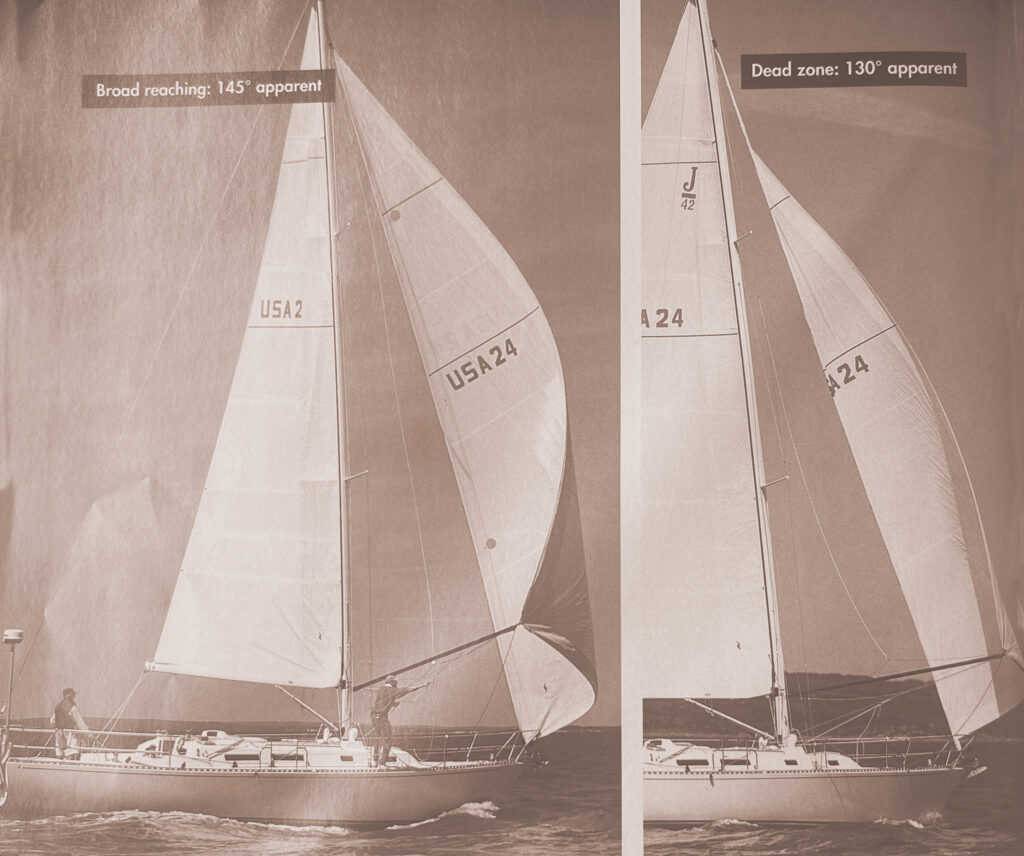

If you try to reach with the pole to windward, the genoa leech twists open and the foot becomes too round because a standard pole is too short. The genoa, at right, is roller-reefed because at 130 degrees, the sail must be smaller to fly without collapsing.

Billy Black/Sailing World Archives

Avoid the Dead Zone

If you try to reach with the pole to windward, the genoa leech twists open and the foot becomes too round because a standard pole is too short. The genoa, at right, is roller-reefed because at 130 degrees, the sail must be smaller to fly without collapsing.

Billy Black/Sailing World Archives

Avoid the Dead Zone

The dead zone is the reaching angle at which the genoa won’t fly properly whether it’s poled out to weather or to leeward. In the dead zone, your boatspeed suffers no matter what you try.

For boats with a 150-percent genoa and a standard pole, the dead zone should occur at apparent wind angles of 120 to 135 degrees. It can be found by poling the genoa out to leeward on a beam reach, then slowly bearing off until the sail begins to go limp. If you try to sail wing-and-wing at this angle, the pole will have to be set so far forward that the foot of the genoa will be unnaturally full.

When faced with a leg lying at an angle in this dead zone, don’t sail straight at the mark. Instead, reach high of the rhumbline, at an angle of 110 degrees, but the poled denoa lower. Then, when the bearing to the mark is such that you can fetch it at an apparent wind angle of 135 degrees, bear off and reset the pole to windward. The exception to this would be in extremely light air, when you should continue at 110 degrees until the mark could be fetched at a 110-degree angle on the opposite jibe. When this point is reached, jibe for the mark and reset the pole to leeward on the opposite jibe.

Don’t Sail Dead DownwindJust like sailing with a spinnaker, it rarely pays to sail dead down, wind with cruising canvas, even on a leg, which is a dead run. By heading up a certain amount, your boat speed climbs to a point where it will pay to jibe back-and-forth to a lower mark. This is called “sailing to polars,” a concept that most spinnaker trimmers recognize. The proper polar angle depends on the wind strength and your particular boat. However, the angles we discovered for Gannet should be similar for any boat with a 150-percent genoa and a standard-length whisker pole.

No matter what the boat, the lighter the wind, the higher the proper sailing angle will be. And remember, always avoid sailing in the dead zone. In winds under 8 knots, pole the jib out to leeward to sail above the dead zone, maintaining an apparent-wind angle of 100 to 110 degrees. When the wind reaches 8 knots, then it’s time to go wing-on-wing, sailing at an apparent wind angle of 140 degrees, or just below the dead zone. As the wind builds you must sail lower and lower for optimum angle. At 12 knots, the apparent wind angle is about 150 degrees. In 15 knots, it’s 160 degrees, and at 18 knots, it’s 170 degrees. Only in winds of 20 knots or more should you sail dead downwind.

As you can see, there’s more to cruising canvas racing that meets the eye. So, the next time the competition throws up the whisker pole and settles back with a cold brew, ask yourself: “Is this the best angle to keep the boat moving? Am I in the dead zone?” And, “I wonder how that beer will sit if I roll over them with my jib polled out to leeward!”

The post A New Angle on Speed: Poling the Headsail appeared first on Sailing World.

- Home

- About Us

- Write For Us / Submit Content

- Advertising And Affiliates

- Feeds And Syndication

- Contact Us

- Login

- Privacy

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.