Buyers Beware: Navigating the Boat Purchase Process

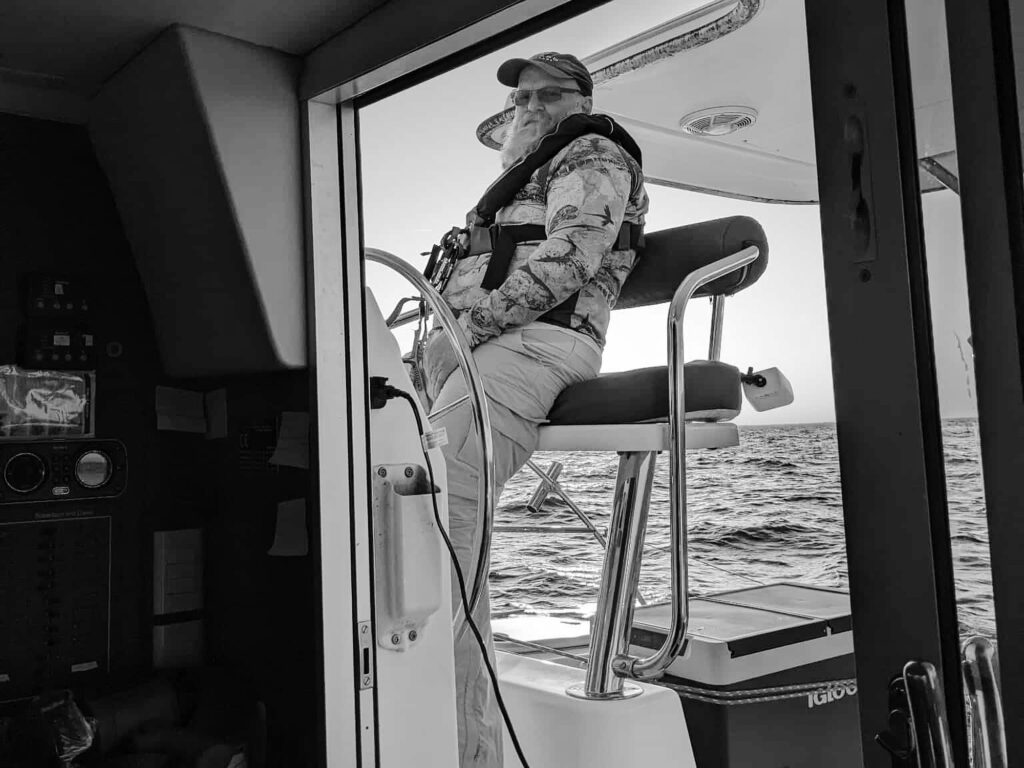

Matt Rabdau sits at the helm of the Leopard 38 Chinook, downsized from his and his wife’s original dream boat to stay on budget and upgrade smartly for life under sail.

Colette Rabdau

Matt Rabdau sits at the helm of the Leopard 38 Chinook, downsized from his and his wife’s original dream boat to stay on budget and upgrade smartly for life under sail.

Colette Rabdau

Here’s a hopeful cruiser sentiment: “I don’t want a project boat; I want one that’s ready to go.”

It’s a fair wish. Who wouldn’t want to skip the difficult refit and head off over the horizon? But a truly turnkey used cruising boat is more myth than reality.

We’ve seen dreamers who buy budget-friendly project boats get overwhelmed with the unexpected effort or cost and never leave the dock. Similarly doomed are the Pollyannas who buy that “ready to go” boat, only to borrow from their cruising kitty to correct myriad problems.

These are not cautionary tales. They’re more typical than not. Buying a cruising boat can be one of the biggest purchases in a lifetime, but unlike buying a house or a car, the search can be slower, messier and more emotional. Getting it wrong can cost thousands of dollars and multiple cruising seasons.

Let’s talk about how to get this purchase right.

The Right BoatSpoiler: There is no “best” boat for cruising. There isn’t even a “correct” set of features. It’s easy to get trapped by dogma, and much conventional wisdom is dated when it comes to what makes a bluewater boat. Just ask an AI bot, which feeds on outdated content and parrots a misleading response. Eventually, it will learn that a full or modified keel and heavy displacement hulls are not essential features for an offshore cruising vessel.

Retaining old-school biases limits the inventory of candidate boats. Modern build techniques and design innovations give better sailing performance, more living and cockpit space, and an easier path to insurance. Helping people release biases around legacy bluewater design is a theme that we visit repeatedly in our coaching service.

What’s real is the boat that’s right for a particular buyer. To find that sweet spot of features, real feel and budget, start by envisioning cruising goals. Is the plan coastal or regional, such as the Caribbean, the Mediterranean or Mexico? Or are you thinking about crossing oceans and doing some multiregional cruising? Safety offshore has more to do with the sailor’s choices while cruising than with the make of boat.

Bob and Kim Stephens, currently cruising in the South Pacific aboard their Stevens 47, Meraviglia, say there are often mismatches between boats and sailors. They underscore that not all buyers are created equal: A buyer who knows boats, has owned boats, and has experience with boats is a significantly different buyer than one who is new to boating. Knowing yourself, including your skillset and risk tolerance, is as important as knowing your boat in determining the outcome.

The All-In BudgetTo work out whether a boat fits in your budget, start with a purchase figure, then add a general rule to estimate the additional refit budget.

Oh, wait—there is no general rule for refit cost. Every boat is different, and oversimplification will gloss over the likely budget necessary to make a cruising boat safe, reliable and comfortable.

Instead, consider the total cost to purchase and equip a boat for your intentions. We call this the all-in budget: the total investment needed to purchase andprepare the boat for use. It includes purchasing costs beyond the negotiated price, such as survey and haulout, along with transaction fees, taxes, maybe delivery to another location, and the first year’s insurance.

The refit is fixing known and surprise faults, adding missing gear, and replacing unsuitable or aged-out gear. Costs can add up, and new cruisers can hemorrhage money to reach departure day. Before committing to any boat, thoroughly assess its condition and gear to estimate refit costs. We use a spreadsheet template with fields for available budget, all purchase costs, and refit cost estimates broken down in categories, such as anchor gear, energy systems and rigging.

There is no “best” boat for cruising. It’s easy to get trapped by dogma, and much conventional wisdom is dated when it comes to what makes a bluewater boat.

If the all-in costs exceed the budget ceiling, then it’s time to negotiate a lower price, recalibrate to a different boat, or plant a money tree.

Going through this process to vet a boat can be liberating or frustrating. Make sure the heartstrings tugging over the quality workmanship don’t overshadow the voice mumbling about the rigging age, lack of safety, and energy systems meant for being tied to a dock rather than off the grid.

Finding a BoatBuyers often ask us where they should look. Online listings are a typical choice, and there are dozens of sites to browse. We track around 30 in our lists. A few sites list only brokered boats; others focus on private sales or specific regions, such as North America, Australia or Europe.

A boat search doesn’t have to be limited to where you want to start cruising. Identical boats are likely to be priced differently depending on whether they’re in Florida, Maryland or Connecticut. It might make sense to cast a wider net and factor in the cost of relocation after purchase, especially if you’re not finding candidate boats in your local search area.

Consider starting where the better-fit boat is, even if it’s not your originally planned location. Many buyers feel more comfortable purchasing a boat they can drive to. One common use case is the North American buyer who dreams of cruising the Caribbean. Purchasing to start on the East Coast feels easier and safer than buying a boat in Grenada. But to reach Grenada, the Florida sailor will go more than 1,000 nautical miles against prevailing conditions on the so-called Thorny Path.

Jamie Gifford of Sailing Totem and Suky Cannon give Shambala’s gooseneck a close look while evaluating the boat for purchase.

Courtesy Behan Gifford

Jamie Gifford of Sailing Totem and Suky Cannon give Shambala’s gooseneck a close look while evaluating the boat for purchase.

Courtesy Behan Gifford

One Seattle-area couple we supported as coaches, Matt and Colette Rabdau, began their search focused on Leopard 44 catamarans. Colette made several trips to Florida, where, despite having watched video walk-throughs, she found gaps that drove up refit costs. They scaled back to smaller models with lower price points to allow more buffer in their funds. Ultimately, they acquired a Leopard 38.

“We were glad that we shifted from a 44-foot boat to a 38-foot boat, as the money we did not spend was available to make other repairs, including replacing both fuel tanks, the front windows, all four cabin windows and portlights,” they told us via email. They also did some upgrades, adding Starlink, a higher-output alternator, a LiFePo4 bank and a watermaker.

Now two years into cruising the United States and Bahamas aboard Chinook, they say it was the right call to recalibrate. “If we had purchased the 44 [dream boat],” they write, “we would not have had the necessary funds for the upgrades and repairs that would likely have come up for other boats as well.”

Digging Into ListingsIt’s tempting to treat a boat’s equipment list in binary fashion: Gear is either there or it isn’t. To avoid surprise expenses after a transaction, buyers should get a deeper understanding of each item’s condition.

Many listings have checkbox lists instead of details. “Depth sounder” seems great, but what kind is it? How old? Similarly, an “autopilot” might be a bungee cord and a centered wheel. Maybe the listing says: “new batteries, 2019.” Well, are they lead acid or lithium? If they’re lead acid, they’re likely near their end of life—not exactly new or a selling point.

Look carefully at photographs. Do the pictures show a pristinely painted engine? Overspray on parts not meant to be painted, such as formed hoses, suggests new paint on a not-new engine. Is this paint covering rust and corrosion from poor maintenance? And is the mainsail fully covered in those dockside images, or is the leech exposed and baking in the sun? How rusty is the anchor chain?

Everything on a boat has a lifespan. As the buyer, you want to know where each item is on that timeline. This depends on the original quality of the item, how well it was installed, and how well it was maintained.

Lifespan applies to nearly everything, not just the electronics. Our boat, the Stevens 47 Totem, is 43 years old. It’s been under our ownership since 2007, and we’re on the third standing rigging, the second engine, the third life raft, the third watermaker—not to mention bulkhead repairs, tank replacements and more.

Many listings have checkbox lists instead of details. “Depth sounder” seems great, but what kind is it? How old? Similarly, an “autopilot” might be a bungee cord and a centered wheel.

Buyers need detailed knowledge, or solid guidance, to assess each component’s stage of life. When a listing is thin, seek information from the seller or their representative. Sometimes, lifespan will be called out for them, such as when an insurance underwriter refuses to bind a policy until an aging rig is replaced.

Digging into listings also means researching online history. One of our coaching clients went through social media posts by the seller of a boat they were considering. It turned out that the boat had been through a hurricane and sustained meaningful damage—so much so that the insurance company had totaled the boat. This information was not disclosed in the listing. They asked pointed questions of the broker. Screenshots supported their case after the seller deleted the content online. The state in which the boat was listed may not have required disclosure, but the code of ethics for professional yacht-broker associations does—as does a basic moral compass.

Again, the goal is to understand the boat’s all-in cost. This cannot be done by applying a general figure or a percentage calculation. It is unique to every boat.

Working With a BrokerA good broker is a valuable asset during the purchase process. The broker provides market insight and access to the back-end data for some online listings to help inform your offer.

The broker also acts as a buffer in negotiations with the seller and their broker. Owners are often emotionally attached to their boats. Explaining why your lower offer for their lovely vessel is fair can be difficult to do directly. After the survey and sea trial, brokers can again save you thousands by negotiating for adjustments to the accepted offer.

Why doesn’t every buyer have a broker? It requires a reasonable budget to make the commission. This is often around the $150,000 mark. Not all brokers want to be a buyer’s representative. It’s not as lucrative. Their commission is paid by the seller.

It’s also important to know what brokers don’tdo. Don’t expect them to scour listings to find that dream boat for you. That responsibility lies with the buyer, although a good broker will assist the process. And, of course, they will know what their own brokerage has available.

Working with a buyer’s broker isn’t always a slam dunk. The Chinook crew’s Seattle-based broker did not advise them effectively about Florida taxation, an omission that cost them a considerable sum.

Resale ValueAvoid problems later by keeping resale in mind before you purchase. Consider demand: Is the make or model a name that people will type into search engines? Does the boat have an owners group? Resale value has geographic implications too. Designs revered in one region are undesirable in others.

An unusual boat—your “unicorn”—might be harder to sell later. The cost to carry a boat for sale, from dock fees to insurance, can get expensive. Boats often sit on the market for months.

Also important: Refit expenditure does not add dollar-for-dollar to resale value. A given make and model tends to have a market value. It will have some regional variation. It will sell faster or slower based on how well it is equipped or maintained. But $150,000 put into a $100,000 boat does not make it worth $250,000.

Newer cruisers aboard their Beneteau, Paradise II, Chris and Shiela say that physically getting onto as many boats as they could was an invaluable part of the process. “Any boat,” Chris says. “Boats I could afford with change from the couch, and boats I couldn’t afford even if I sold both kidneys. Shiela suspected that she would not have been happy with a linear galley, and I knew I wouldn’t be happy with anything in the way from the forward cabin to the companionway stairs.”

Those preferences knocked out lots of designs, but they helped to identify which boats they could afford and which of those retained market value.

When To Pull the TriggerAnalysis paralysis is real. How do you break that cycle and commit to a boat?

Internalize the idea that there is no ready-to-go boat, and then move ahead with due diligence and support. A mentor can help you ask the right questions, and can sometimes answer them too.

Most important, make sure you buy with your head as much as your heart. A particular boat might pull your heartstrings, but do the math on the probable cost to make it ready for your dreams, and learn as much as possible about what you’re getting into.

Then, the day you step aboard your magic carpet really will be one of the best days of your life.

The post Buyers Beware: Navigating the Boat Purchase Process appeared first on Cruising World.

- Home

- About Us

- Write For Us / Submit Content

- Advertising And Affiliates

- Feeds And Syndication

- Contact Us

- Login

- Privacy

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.